Back in 2017, when my first book, Little Gold, was published I took part in a radio interview. This was a new experience for me and among the questions was this,

‘If this story happened now, do you think Little Gold might be called ‘they’, or…?’

There’s a recording so, if you like, you can hunt down exactly what I said in response. But I can remember the gist. I said something like,

‘She’s twelve in the book, she’s undefined… I think she’s happy to be a girl, I think…’

My mouth stumbled about as a voice whispered in my mind,

‘Careful, careful, don’t get it wrong…’

What on earth was that whispering voice? How might I ‘get it wrong’ about my own character in my own book?

Well, I was aware, I remain aware, that wrong lurks inside me. Fear of it has often shut my mouth, stilled my pen or my hands on the keyboard. This particular wrongness is, at its heart, what Little Gold feels in the book. She knows she’s not what is expected of a girl. I knew that about myself as a child and it persists in my life as a woman.

When we feel wrongness inside us, we must be circumspect. We must be ever-measured and ready, always, to curtail our words. We must not go too far. We must soften edges and do our best not to cause offence.

But in the year since that radio interview I have done a lot of thinking about how I answered that question on Little Gold’s gender. I have considered the place that my book holds in the world, just one story about a ‘boyish girl’ in the summer of 1982, published by a small press and hardly taking the world by storm, but still a published book, my book.

So, ask me again about Little Gold and now I will say this,

‘Little Gold is a girl. Little Gold is a girl being told she is the wrong kind of girl by the world in which she is growing up. But Little Gold is a girl with nothing to be ashamed of and nothing that needs fixing.’

I want this message stated explicitly because it is a message too close to my heart, to myself, to mutter or mumble. Because, just now, there is a new way that girls like Little Gold might feel themselves to be wrong.

In our society today there are more people coming out as trans and there are increasing numbers of stories of transition. Good luck to those who have those tales to tell. But that is not the story of Little Gold.

The story of Little Gold takes place over a single summer when the protagonist is only twelve. But what I hope readers understand through her experience, and that of her elderly neighbour Peggy Baxter, is this:

There are girls who are ‘boyish’, who remain that way all through childhood, who struggle through puberty and fall in love with other girls.

Those girls become women who go on to live their whole lives as the butch women they are. They make rich lives. They are not ‘half way’ to something else, they are not ‘women who want to be men’, but simply women on their own terms.

I know, I know from my own life, that girls like that need assurance that such a life is possible. That is the gift that Peggy Baxter gives Little Gold and I, as the creator of those two characters, want to state that message too. Because to imply anything else feels like a betrayal of them. And, more than that, it feels like a betrayal of myself.

So, here is a ‘boyish girl’ growing up and some things I happen to know about her.

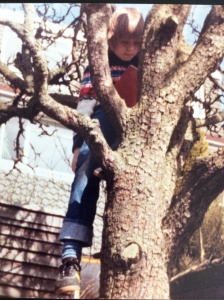

Ten. In the tree. She’s reading a book about posh girls at boarding school. She is fond of her body, straight up and down with a tea-stain birth mark. She’s Mr Toad in the school play that year.

Eleven. On a canal boat holiday with extended family. She is filled with rage that she doesn’t have the upper-body strength to open the lock gates like her older brother and male cousin. She throws her glasses into a field from the top of the boat. Her uncle says,

‘I thought you were a nice little girl before we went on this holiday.’

Shame of wrong stops her mouth entirely. She doesn’t know what she is, after all. Puberty has arrived but the shirt is baggy to hide the breasts she tries not to look at. Her body makes new, alien scents. She gets dressed in the tiny toilet.

Twelve. Staying in youth hostels around The Netherlands. Inside the neck purse is a scented sanitary towel. This is only the second period she has ever known. It seems impossible that it will happen every month from now on. That year, a man has touched her breast and she feels she has become some sort of prey. It is all quite sickening but she likes those clogs. Those clogs are funny.

Fourteen. She has met death and grown up fast. She reads about women who are mad, to see if she might be mad. She decides she is not but falls in love with a picture of a woman’s face on the cover of Antonia White’s ‘Beyond the Glass.’ She says a word to try it out and knows, instantly, it is her. ‘Lesbian.’ It tastes sweet and forbidden on her tongue but she isn’t scared of it. She starts to write, books and books of writing that no-one ever reads. All her wrongness is on the paper and the book is closed.

Fifteen. On a family holiday in the Lake District she spends as much time as possible with her Walkman on. Looking out of the car window, Joan Armatrading in her ears, she fantasises about kissing a girl she loves. She curls her secret life in her hand, see? Too tense to even stand on both feet. Her cousin asks his mum,

‘What does heterosexual mean?’

‘Normal. A man and a woman. Normal.’

She presses play again and looks out at the horizon.

Let’s leave her there at fifteen. It’s true she’s yet to kiss a girl but she has a rich imagination and she’ll get by until she does. She will ditch that Genesis t-shirt quite soon but never really take to girls’ clothes. Her hair won’t ever be much longer. Life will go on.

Will she always be well, strong, certain? No. She will sometimes doubt everything about herself. Shame will gnaw her from the inside. She can’t pass through this vicious world unscathed because no-one can. She will have some vulnerabilities that come from being what the world calls a contradiction. But she will live her life. She’ll grow a baby in that body and feed it from the breasts she’s never liked much. She’ll learn to respect them for that piece of magic.

She will keep writing but it will take a lot of years until she shows her words to anyone else. And, when she does, she will have to learn the resilience needed to be in the public gaze. She will wonder if she shouldn’t say too much, shouldn’t risk upsetting anyone, if, perhaps, even now, she’s wrong.

But then she’ll write these words and know they’re true and that she should not, must not, apologise for them. Little Gold is a girl. Little Gold is a girl with nothing to be ashamed of and nothing that needs fixing.

Brave, honest and thoughtful. I have always admired and loved you (and right now I do both just a little bit more!!) xxx

I love you too xxx

Little Gold was not alone and I am sorry she didn’t know that then. Love your writing and your/her boldness and long live all the Little Golds everywhere!

Women like you, women who wrote books, helped me figure out a lot of things. Without 1980s feminist presses it would have been much harder.

Just like Han, I love you too. I really hope you know that. I was so lucky to be around when you and I were growing up. Xxx

I was always so glad you were there. No-one laughed like you. And all thos illicit cigs… 😀 Lots of love x

This is beautiful Allie

I love the way you write, and what you write – the straight-to-the-heart clarity of it, apart from anything else. I’m going to buy the book now.

Really well written and needs saying – wonderful and inspiring!

I’ve just finished you’re beautiful novel and was craving more of your writing so very happy to have found this well written article that is beautifully honest and to the point. I have so much love for Little Gold’s character as well as your portrayal of my hometown. It must be so hard to be in the public eye so well done for sharing the importance of sticking to your voice that resonates within the novel. You are brilliant. I very much look forward to meeting you at the book club event. With love and admiration, chloe.

Thank you so much, Chloe. I’m looking forward to meeting you too. All the best, Allie